Shoulder pain can affect much more than just our comfort. It can limit our ability to pick up our children, carry groceries, or even reach for something on a high shelf. If you’ve been struggling with nagging shoulder pain, there’s a strong possibility it may be due...

A stress fracture is a small crack within a bone. However, unlike acute fractures, which occur from a sudden injury, stress fractures gradually develop over time and are common among athletes, runners, and individuals with physically demanding lifestyles. These tiny,...

Tendons are tough, fibrous tissues that connect muscle to bone and play a critical role in our movement, from helping us swing a tennis racket to allowing us to lift groceries or climb the stairs. But for all their strength and flexibility, tendons are also...

High Ankle Sprain: Different Than Your Average Ankle Sprain

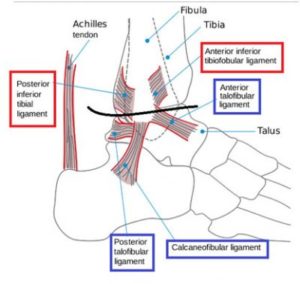

Ankle sprains are one of the most common injuries treated by the foot and ankle physician, accounting for approximately 20-40% of all athletic injuries.1 This typically consists of a sprain of one of the three lateral ankle ligaments (Fig – BLUE; below black line): anterior talofibular (ATFL), calcaneofibular (CFL), or posterior talofibular ligament (CFL), each defined by the direction they occur and bones they connect. ATFL sprains occur 70% of the time with ATFL and CFL simultaneous sprains 20% of the time. The PTFL is rarely sprained at less than 5-10% of the time.1,2

Different than the lateral ankle ligaments that are described above, the high ankle sprain consists of injury to one of the syndesmotic ligaments (Fig – RED; above black line): anterior inferior tibiofibular (AITFL), interosseous (IOL), posterior inferior tibiofibular (PITFL), and inferior transverse ligament (ITL). These ligaments are important in keeping the distal ends of the two long bones of the leg, the tibia and fibula, together so the ankle remains stable. Syndesmotic sprains occur anywhere between 10-32% of all ankle sprains, higher in the athletic population.1 While lateral ankle sprains are a result of inversion of the ankle, high ankle sprains typically have an additional component of rotation of the foot or leg. A specific set of physical exam tests will be performed by your physician to test the existence of a high ankle sprain injury (“squeeze test,” “external rotation test,” and “crossed-leg test”).

Most of the time, the doctor will first start his or her evaluation with an X-ray to rule out a broken bone in the ankle or foot. Certain bony relationships cue the doctor into potential ligamentous injuries. A CT or MRI may be additionally ordered depending on the X-ray findings, physical exam findings, and mechanism of injury to assess the ligaments and tibia and fibula relationship at the syndesmosis.

It is important to remember with any ankle sprain that healing is not instant. It is key to protect the ankle in the first 2-3 weeks of healing followed by physical therapy to strengthen both the ligaments in the ankle and the muscles of the foot, leg, and thigh. Ligaments need one year to restore original mechanical strength. Scar tissue that forms following a sprain will take 6-12 weeks to mature to sport tensile strength. It is also important to differentiate a lateral ankle versus high ankle sprain as the treatment protocol for each is different with the high ankle sprain often requiring more initial rest and immobilization (sometimes twice that of a lateral ankle sprain) before starting therapy. These injuries often have a more delayed return to sport by several weeks. In some instances, severe syndesmotic injuries require immediate surgical correction.

After a first sprain, 70% of people will have a repeat sprain at some point and 40-50% of sprainers will have some long term symptom (decrease ROM, pain, swell, weakness, lateral ankle instability), specifically with Grade 2-3 sprains. In syndesmotic injuries, symptoms can remain for up to 6 months after the incident. Furthermore, recurrent sprains (2-3/year) can lead to a condition called lateral ankle instability that often requires surgical correction to tighten the ligaments. It is important to undergo guided physical therapy to safely progress through the healing process and assess when it is appropriate to return to activity (ie. sport).

| Classification System | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

| Dias | Partial Rupture CFL | Complete Rupture ATFL | Complete Rupture ATFL, CFL, ± PTFL | All 3 Lateral Ligaments + Deltoid (Partial, Complete) |

| Leach | Partial/Complete ATFL Tear | Partial/Complete ATFL + CFL Tear | Partial/Complete ATFL + CFL + PTFL Tear | |

| Dubin et al.1 | Microscopic Tearing of ATFL | Microscopic Tearing of Larger Cross-Section Portion of ATFL | Complete Rupture of ATFL; Microscopic or Complete Failure of CFL |

If you have been dealing with an ankle sprain, whether it is your first or a recurrence, or have continued ankle pain, schedule an appointment with a foot and ankle specialist to discuss your treatment options. Furthermore, if your ankle feels unsteady and you chronically sprain, you may have chronic lateral ankle instability with harm not just to the ligaments about the ankle, but the bones/cartilage, joint, and tendons as well. Your doctor will help you determine a personalized treatment plan for you.

Dr. Hood is a fellowship trained foot and ankle surgeon. Follow him on Twitter at @crhoodjrdpm.

Image credit from:

- Sprained Ankle. 2015. Available at: < http://www.thevisualmd.com/panel/?c=719.37>

References:

- Dubin JC, Comeau D, McClelland RI, Dubin RA, Ferrel E. Lateral and syndesmotic ankle sprain injuries: a narrative literature review. J Chiropr Med. 2011;10(3):204-219. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2011.02.001.

- Golanó P, Vega J, de Leeuw PAJ, et al. Anatomy of the ankle ligaments: a pictorial essay. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):944-956. doi:10.1007/s00167-016-4059-4.

Christopher R. Hood JR, DPM